Gluten – Not For All Gluttons!

Prelude

I am sure you have heard people complaining how hard it is for them to avoid pizza, cakes, parathas and egg rolls. What is common among such wheat-based products is a substance called gluten. But what, exactly, is gluten? Why is it important that certain people avoid gluten at all costs? The answers to these questions involves a long story, so read ahead to find out more. By the end, you might also be able to provide some hope to your gluten-deprived friends and help them rekindle their taste buds!

The What and When of Gluten

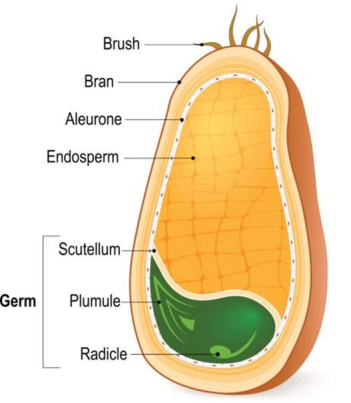

Gluten is the rubbery mass that remains when wheat dough is washed with water or brine solution to remove the starch from it. It is a complex mixture of hundreds of different proteins present in wheat grain or similar grains like rye, barley, and oats. These grain-storage proteins are exclusively found in the endosperm of wheat kernels and their role is to help the germination of seeds. The amount of gluten present in wheat depends upon its variety, the time of harvest and its geographical location.

Different parts of a wheat grain. Source

Different parts of a wheat grain. Source

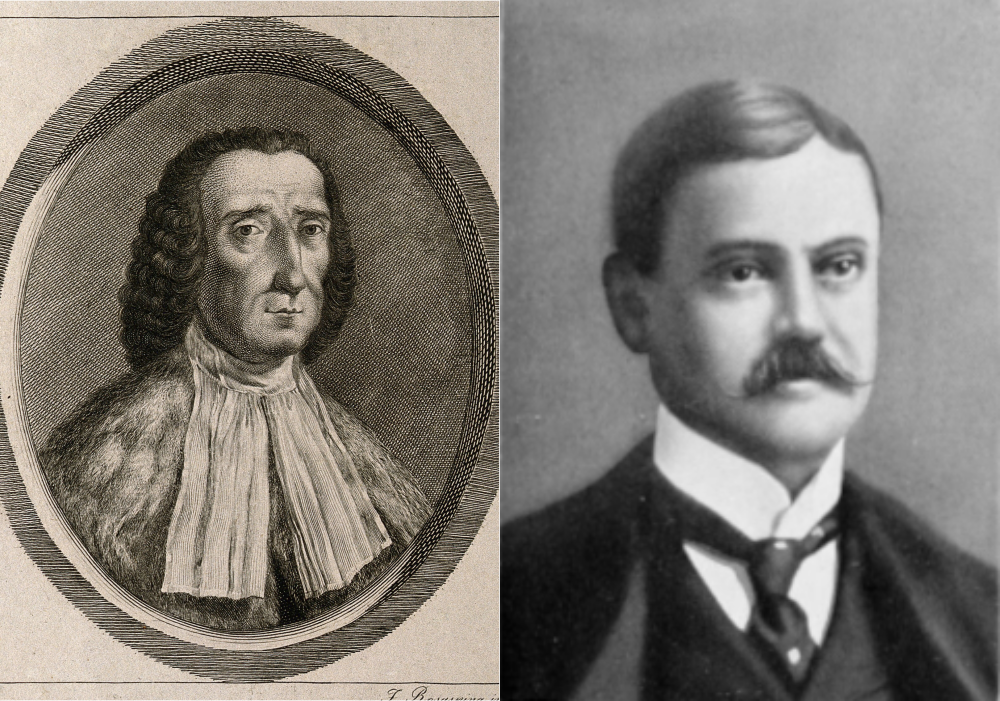

Wheat gluten is in fact one of the earliest scientifically studied proteins. The first such study was conducted back in 1745 by Jacopo Beccari, a chemistry professor at the University of Bologna. Before the 1970s, the decade when the process of gel electrophoresis was developed, a Connecticut-based plant protein chemist Dr. T. B Osborne successfully extracted proteins from a variety of seeds in a series of solvents of varying polarity between 1886 and 1928. His technique, known as the Osborne fractionation, is still in use to this day. Osborne discovered that the four fractions of proteins are albumins (soluble in water), globulins (soluble in dilute saline), prolamins (soluble in 60–70% alcohol), and finally glutenins (insoluble in other solvents but may be extracted in alkali). He coined the term prolamins to refer to a certain category of proteins as he found high content of amino acid like proline in them. He was able to classify prolamins into subtypes, based on the cereals in which they occur: gliadin in wheat, hordein in barley, secalin in the rye, zein in maize, etc.

Jacopo Beccari (left, source) and T.B Osborne (right, source).

Jacopo Beccari (left, source) and T.B Osborne (right, source).

The Chemistry of Gluten: Gliadins and Glutenins

The primary constituents of gluten are gliadin and glutenins, collectively referred to as prolamins. The genes involved in the synthesis of the gluten proteins inside a grain of seed are - the Gli-1 and Gli-2 loci coding for the gliadin proteins, plus the Glu-1 and Glu-3 loci, coding for the glutenin polypeptides. At a molecular level, gliadins are monomeric proteins that have molecular weights (MW) around 28,000 to 55,000 respectively whereas glutenins are polymers, particularly of high molecular weight subunits that have a varying weight of around 67000 to more than 88000 respectively.

The study of the polymers of glutens is particularly relevant to the preparation of bread which is a staple food across many cultures worldwide. Gluten proteins are highly hydrophobic and show a preference to bond with the lipids compared to water. However, in the context of the dough, compared to the glutenins, hydrated gliadins are very less elastic and less cohesive; they contribute mainly to viscosity and extensibility. Hydrated glutenins on the other hand are both cohesive and elastic and are responsible for dough strength and elasticity. To put it simply, gluten is a bi-component adhesive, in which gliadins act as a solvent for the glutenins.

Formation of gluten. Source

Formation of gluten. Source

Gliadins are broadly subdivided into three broad types. α/β, γ and ω-gliadins. The distribution of these types varies according to the genotype and growing conditions of wheat such as climate, soil, and fertilization. It can be said that the α/β- and γ-gliadins are major components compared to the ω-gliadins.

Upon deeper inspection, gliadin proteins have almost entirely repetitive sequences rich in glutamine and proline (e.g., PQQPFPQQ)[2]. α/β- and γ-gliadins have similar molecular weights and have a significantly lower amount of glutamine and proline than ω-gliadins. Each of both types has two different N and C-terminal domains. The N-terminal domain (40–50% of total proteins) consists mostly of repetitive sequences rich in glutamine, proline, phenylalanine, and tyrosine and is unique for each type. The repetitive units of α/β -gliadins are dodecapeptides such as QPQPFPQQPYP which are usually repeated five times and modified by the substitution of single residues. The typical unit of γ-gliadins is QPQQPFP, which is repeated up to 16 times and interspersed by additional residues. Within the C-terminal domains, α/β - and γ-gliadins are homologous. They present sequences that are non-repetitive, have less glutamine and proline than the N-terminal domain, and possess are more usual composition. Studies on the secondary structure have indicated that the N-terminal domains of α/β - and γ-gliadins are characterized by β-turn conformation, similar to ω-gliadins. The non- repetitive C-terminal domain contains considerable proportions of α-helix and β-sheet structures.

On the other hand, glutenins are made up of both high molecular weight polymers and low molecular weight subunit polymers truncated from the higher counterparts. The proportion of low molecular weight glutenin subunits (LMW-GS), their proportion amounts to E20% of the total gluten proteins. LMW-GS are similar to α/β and γ-gliadins in terms of molecular weight and amino acid composition. They also contain two different domains: The N-terminal domain consists of glutamine- and proline-rich repetitive units such as QQQPPFS and the C-terminal domain is homologous to that of α/β - and γ-gliadins. LMW-GS contains 8 cysteines, and 6 residues are in locations similar to α/β - and γ-gliadins. Hence, they are proposed to be linked by an intrachain disulphide bond. High Molecular weight glutenin subunits (HMW-GS) belong to the minor components within the gluten protein family (E10%). Each wheat variety contains 3 to 5 HMW-GS which can be further divided into two different types, the x- and the y-type, with MWs from 83,000–88,000 and 67,000–74,000 respectively.

Furthermore, the nomenclature of a single HMW-GS is based on the coding genome (A, B, D), the type (x, y), and the mobility of SDS-PAGE. HMW-GS consists of three structural domains: a non-repetitive N terminal domain (A) comprising about 80–105 residues, a repetitive central domain (B) of about 480–700 residues, and a C-terminal domain (C) of 42 residues. Domains A and C are characterized by the frequent occurrence of charged residues and by the presence of most or all cysteines. Domain B contains repetitive hexapeptides (unit QQPGQG) as a backbone with inserted hexapeptides (e.g., YYPTSP) and tripeptides (e.g., QQP or QPG). The most important difference between the x- and the y-type lies within the A and B domains. For example, the y-type has an insertion of 18 residues including two neighbouring cysteines in domain A, and typical repetitive units are less frequently repeated and more frequently modified in domain B of the y-type. As HMW-GS does not occur in flour and dough as monomers, it is generally assumed that they form interchain disulphide bonds. The x type except subunit Dx5 has four cysteines, three in domain A and one in domain C. These were predicted to be overlapping and form a loose spiral which was considered to contribute decisively to gluten’s elasticity. The non-repetitive domains A and C were proposed to have globular structures containing a-helices. Among HMW-GS the contribution of the x-type to dough properties is more important than that of the y-type. Considering single subunits, the presence of subunit Dx5 (which has extra cysteine for an inter-chain crosslink) and subunit Bx7 (which occurs in the greatest amounts) has been proposed to be particularly important for dough quality and loaf volume. Fun fact, the largest polymers termed ‘glutenin macropolymer (GMP) make the greatest contribution to dough properties and their amount in wheat flour (E20–40 mg/g) is strongly correlated with dough strength and loaf volume.

Harmful Effects of Gluten

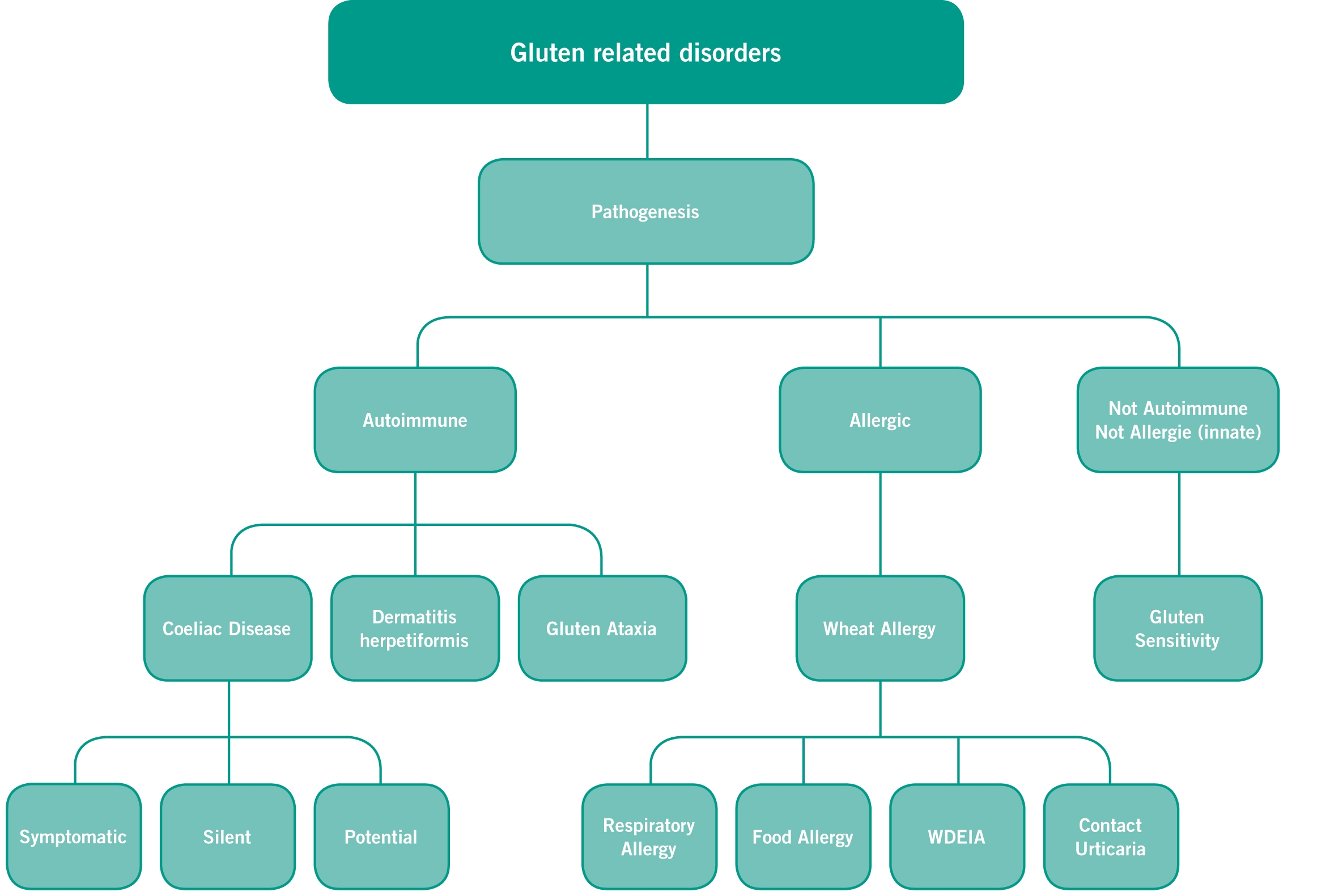

It is indeed unfortunate that some people are ill-suited to consume gluten-based products. Owing to the presence of some toxic peptides, gluten is the cause of a plethora of health disorders like celiac disease, wheat allergy, gluten sensitivity, gluten ataxia and dermatitis herpetoformis. Some papers also report aggravated schizophrenia, mood shifts, and psoriasis.

Flowchart showing various health disorders related to gluten consumption. Source

Flowchart showing various health disorders related to gluten consumption. Source

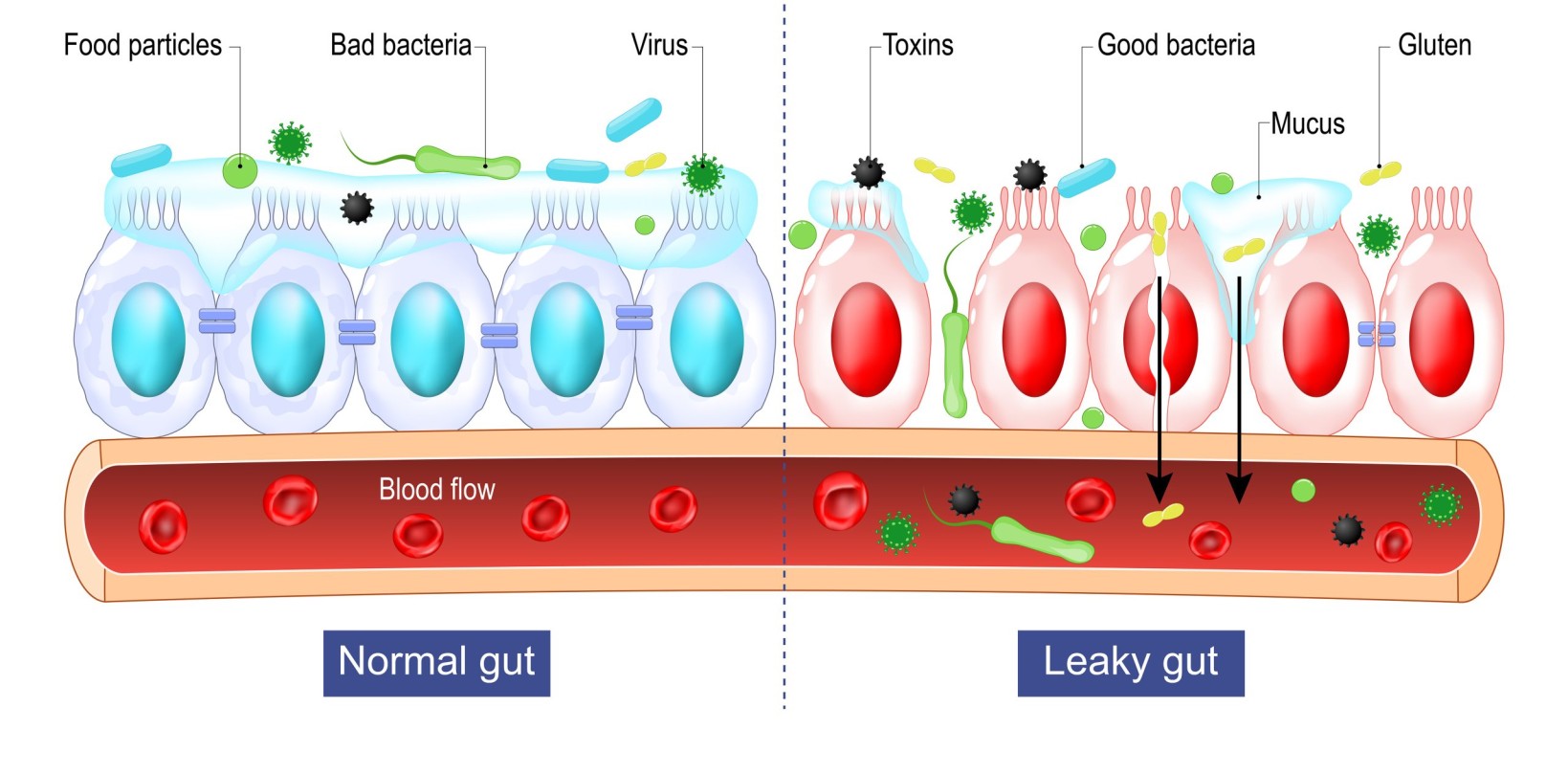

Among all the disorders triggered by gluten, celiac disease bears special mention. Commonly referred to as the leaky gut syndrome, it is a lifelong autoimmune condition where the ingestion of gluten leads to severe inflammation of intestine walls, followed by the loss of villi (structures that absorb nutrients during the nutrition assimilation process). When infected with the celiac disease, the body of the patient produces abnormal amounts of antibodies due to percolation of toxins through the intestinal wall. They also suffer from nutrition deficiency in their diets. Symptoms of this disease include altered bowel habits, nausea and (in some case) paranoid thinking. It is believed that there is a genetic disposition where the disease is triggered in susceptible individuals carrying the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)- DQ2 or DQ8. The only way to alleviate the suffering due to this disease is to avoid gluten-based diets throughout one’s life.

Another gluten-related disorder, gluten sensitivity, leads to increased epithelial barrier function, apart from other symptoms similar to celiac disease. Decreased epithelial barrier function leads to increased permeability of lactulose across the small intestine hence in the patient’s urine and vice versa. In gluten ataxia, a progressive disorder, gluten affects the cerebellum of the brain. It is one of the extraintestinal manifestations of gluten-related disorder observed to date. Gluten in this case leads to paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration thereby affecting limb coordination, speech, and vision. It is also found that in some cases, the cerebellum gets shrunk in size upon gluten consumption. Scientists suggest that antigliadin antibodies damage the central nervous system as post-mortem inspection of affected patients reveals the presence of large amounts of T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes around the cerebellum cortex accompanied by patchy loss of Purkinje cells. Here too, lifelong avoidance of gluten in the diet is a good measure.

Distinction between a normal gut and a leaky gut. Source

Distinction between a normal gut and a leaky gut. Source

Gluten-Free Bread and How To Improve It

The disadvantages of gluten in diet are alarming for many people and cannot be ignored. Gluten-free foods, according to the Food and Drug Administration in the United States, are said to have a gluten content of less than 20 ppm (parts per million). They mainly contain starch either from rice or corn along with fibers, hydrocolloids, and specific enzymes. Gluten-free loaves of bread are severely compromised of nutrients because of high starch and lipid content. Whole grains such as quinoa, sorghum, buckwheat, millet, and amaranth are often added to increase the protein content. Carob germ flour, chickpea flour, and pea isolate are also used in some cases.

Gluten-free bread is often unappealing to consumers due to its low volume, pale crust, bland flavour and crumbly texture, and high rate of staling. Milk proteins are added to improve the elasticity of the dough. Chemically modified starches like Hydroxypropyl distarch phosphate (HDP) and Acetylated Distarch adipate (ADA) help to increase the volume of obtained gluten-free loaves. The addition of linseed mucilage also helps to improve the sensory acceptance of bread. Gluten-free doughs are also subjected to enzymatic treatments. Transglutaminase enzyme can act as a substituent for hydrocolloids when it comes to modifying the protein functionality and cross-linking. Hence it mimics the elasticity of gluten-based doughs. Protease enzymes like bacillolysin, papain, and subtilisin help to increase the load volume by 30 to 60%. The crumb hardness of these bread was also found to decrease by 10-30% compared to untreated ones.

Gluten-free bread. Source

Gluten-free bread. Source

In addition to the previously mentioned methods, sourdough fermentation in gluten-free breadmaking has also attracted the attention of scientists. The peptidase present in sourdough help to detoxify the wheat and rye proteins. It facilitates the extractability of bioactive compounds from the flour. It also enhances the flavor profile of gluten-free bread.

Is There Any Silver Lining Here?

Although discovered some three hundred years ago, gluten has come to the forefront of social attention only in recent years due to gradual awareness of various gluten-related disorders. This has led to the appearance of gluten-free alternatives in the market. While the expense of gluten-free bread is quite high compared to its counterparts and the savoury aspects of these alternatives leave a lot to be desired, the market prospects of gluten-free products are on a gradual rise, and the quest for gluten free alternatives has opened up new avenues for business. It is certainly conceivable that in the not so distance future, people will grow new cultivars of wheat without its toxic polypeptides in gluten. Of course, in order to reach that milestone an in-depth knowledge of protein folding is necessary, in terms of both experiment and theory. In conclusion, I invite the readers to come forward and take up the challenge.

References

- Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2017; 32 (Suppl. 1): 78–81; doi:10.1111/jgh.13703

- Shewry P (2019) What Is Gluten—Why Is It Special? Front. Nutr. 6:101; doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00101

- Food Microbiology 24 (2007) 115–119; doi:10.1016/j.fm.2006.07.004

- Journal of Cereal Science 39 (2004) 395–402; doi:10.1016/j.jcs.2004.02.002

- Arch Gen Psychiatry Vol 39 March 1982

- Trends in Food Science & Technology 17 (2006) 82–90; doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2005.10.003

- Trends in Food Science & Technology 66 (2017) 98-107 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2017.06.004

- Vol. 79, Nr. 6, 2014 Journal of Food Science R1067

- Journal of Cereal Science 29 (1999) 103–107

- Biotechnology Vol. 13 NOVEMBER 1995 “1”185

- Volta, U. & De Giorgio, R. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9, 295–299 (2012); published online 28 February 2012; doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2012.15

- Plant Foods Hum Nutr (2014) 69:182–187 DOI 10.1007/s11130-014-0410-4

- The Cerebellum 2008, – 7 s123 -008-0052-x 2008 Springer Science + Business Media, LLC 11 Online first: 12 September 2008 494 498

- Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 318–30 www.thelancet.com/neurology Vol 9 March 2010

- LWT - Food Science and Technology 63 (2015) 706-713